Across the political spectrum, people are realizing that the digital advertising model pioneered by Google and Facebook poses a growing threat to democracy. These firms know more about citizens of the world's democracies than the Stasi knew about East Germans. They can exploit what they know without relying on the coercive power of a police state. They can adjust what people see and exercise control by a thousand nudges.

In the United States, recent estimates are that Facebook controls 59% of all spending on digital political advertising; Google controls another 18%. In a public conversation in the summer of 2019, Mark Zuckerberg, the CEO and majority owner of Facebook, claimed that Facebook is the only candidate for the role of global arbiter for political discourse. It is the only organization that can work "in partnership with intelligence agencies and election commissions around the world" on "election integrity" because it has built "unprecedented content systems" that are "more sophisticated than what a lot of governments have."

I first learned about Facebook's penetration into political dynamics outside the US at a dinner in Chile. During the discussion, senior members from one of its major political parties attributed their recent electoral success to their use of Facebook's targeted political ads. I asked if they were concerned that a foreign corporation controlled by a single person could have so much influence on their elections. My question did not even seem to register. They seemed to think of Facebook as an arms dealer to which they had preferential access. They were comfortable because they were far ahead of the opposition in understanding how to use the new political tools that Facebook had developed. They did not seem to appreciate that Facebook does not sell these weapons; it is a digital mercenary that is always the one with its finger on the trigger.

Disclosures

I do not consult for or take money from any firm in the tech business. The only consulting fees I've ever accepted for work on an antitrust case were paid by the Department of Justice for work I did on the remedy phase of the Microsoft case, which (I was told) were required by law.

On the basis of what I learned at the dinner in Chile and lessons we all learned about the effects that social media and online advertising had during the US election of 2016, I wrote an op-ed that outlined the policy that I will describe in this post. My interest in the connection between surveillance, individualized advertisements, and political influence was heightened after hearing the comments by Mark Zuckerberg that I quoted in the last section at the Aspen Ideas Festival in the summer of 2019.

After I wrote the op-ed describing this policy, I received support for work on the economics of digital services from the Omidyar Foundation's program Responsible Technology.

In 2020, I also received support from the Rockefeller Foundation for work I did on a "screen and isolate" strategy for virus suppression. You might not think that work on this issue would be even remotely connected to the issues that I address in this post. But over the course of many discussions about how to manage the pandemic, I became concerned about an apparent correlation between connections to the tech industry and unrealistic enthusiasm for mobile tracking apps. I was also frustrated by the absence of systematic disclosure about potential conflicts induced by connections of this type.

The Learned Helplessness of Antitrust Policy

The founding principle of the United States was opposition to unchecked power, but the current reaction to the emergence of the ad-tech giants can best be described as learned helplessness. The law and economics movement has been fostering this can't-do attitude for decades by sending the message, "Forget it, there is nothing you can do. It's the market."

Unfortunately, my own work on economic growth seems to have lent support to the next iteration: "Forget it. There's nothing you can do. Market innovation drives growth."

One exception to the prevailing resignation comes from a new generation of legal scholars who seem to be optimistic that a new round of antitrust actions will finally succeed in restraining the ongoing accumulation of economic and political power of the ad-tech giants and other technology-intensive firms. I do not understand their optimism. They seem to be ignoring the clear signal that the Supreme Court sent in 2018 when it endorsed the fact-free economic theorizing about the hypothetical advantages of platforms that the circuit court used to justify overturning an antitrust judgment against American Express that resulted from an investigation that the Department of Justice initiated way back in 2010.

If the Supreme Court is our ultimate guardian, we really are helpless. Revenue for the ad-tech giants could double and double again in the five to ten years that activists could spend litigating cases against them. And in the end, the ruling from the Supreme Court is likely to be, "Forget it. It's a two-sided market."

Playing Offense

Our defense has failed. It is time to play offense.

In my op-ed from 2019, I argued for a flanking attack on the political power of the ad-tech giants that the legislative branch of government could launch. It could enact a progressive tax on revenue from digital advertising.

All three parts of this strategy are critical to its success. Progressivity is the automatic way to offset the increasing returns on investments in code that give bigger firms an advantage over their smaller rivals. Revenue is a better base than income for any new tax. Income is the difference between revenue and cost, which can be incurred in different places, so there is a fundamental ambiguity about where corporate income. This opens up the possibility of avoiding any tax on income by shifting income from high-tax to low-tax jurisdictions. There is no such ambiguity about sources of revenue. Taxing only the revenue from digital advertising is the best way to encourage firms to switch to less dangerous ways to be compensated for the services they provide.

This tax is clearly not a broad attack on all types of monopoly power. It focuses our energies first on the monopolies with the potential to influence all of our policy decisions.

As far as I can tell, there is no constitutional restriction that would prevent the Congress from adopting this type of tax. It would be an excise tax just like the one that was imposed on tanning bed parlors under the Affordable Care Act.

No credible voices dispute the claim that a sufficiently aggressive tax can create irresistible pressure for firms to engage in tax avoidance. The critics of taxes highlight the potential for tax avoidance. If the goal is to raise revenue, avoidance is bad. But the whole point of the this tax is encourage avoindance. The two most obvious ways to avoid it are to split a company into smaller independent companies or to shift to the type of business model that prevails in markets that are, in fact, efficient -- the model where a buyer can pay to get something from a seller but is free to go elsewhere if the price that the seller demands is less than the value of what it offers.

Everyone expects customers to pay for clothing and cars, yet for some reason, many think it is inconceivable that these same customers will pay for digital services. This belief persists even though firms as disparate as Microsoft, Netflix, Duolingo and Substack have demonstrated that people will pay digital services that they value. (Microsoft's modest amount of revenue from digital ads was the result of its purchase of LinkedIn in 2016.) Moreover, subscription-based firms show that there is nothing intrinsically dangerous about the business of providing digital services. Such firms have no need for a surveillance system that tracks all online activity. None of them attacked Apple for letting its customers choose whether to allow digital tracking. They do not turbocharge animosity as a way to get people to spend more using their services. They don't need a private supreme court to deflect responsibility for corporate decisions with far-reaching political implications. None of their corporate decisions have far-reaching political implications.

Google already offers several services that customers pay for, including a premium subscription for access to YouTube. All a tax on digital advertising needs to do is make the subscription model more attractive; and as a fall back in case a firms persists with the advertising model, to make it more attractive for a large firm to spin out independent new ventures and less attractive for it to grow via acquisitions. To spur movement down both of these paths, all it takes is a tax that is sufficiently aggressive.

In the next section, I'll offer some specifics about the type of tax that I think it will take to create a strong enough incentive for tax avoidance. Then, in the section that follows, you will have a chance to propose your own version of a tax and quantify the incentives for avoidance that it would create.

A Modest Proposal

A progressive tax must specify a base and a schedule of rates. In this post, the base I'll use is the revenue that a firm collects from digital ads that are shown to people in the United States. (In a subsequent post, I'll explore global extensions of such a tax.)

The table belows shows what I mean by aggressive. It describes a tax system with a marginal tax rate that exceeds 70% on advertising revenue greater than $60 billion per year.

To be clear about the mechanics of this type of schedule, consider what it would mean for Twitter and Microsoft. In 2021, Twitter is projected to receive about $2.2 billion for digital ads displayed in the US. This amount falls into the first tax bracket where the tax rate is zero. Twitter would pay zero tax. The projection for Microsoft is that it will earn $6.7 billion for displaying digital ads in the US. Under this tax schedule, it would pay nothing on the first $5 billion in revenue, and 5% on the $1.7 billion that falls into the second tax bracket, hence would owe $0.1 billion to the government. Its average tax rate of 1.25% is its total tax payment of $0.1 billion divided by its ad revenue of $8 billion.

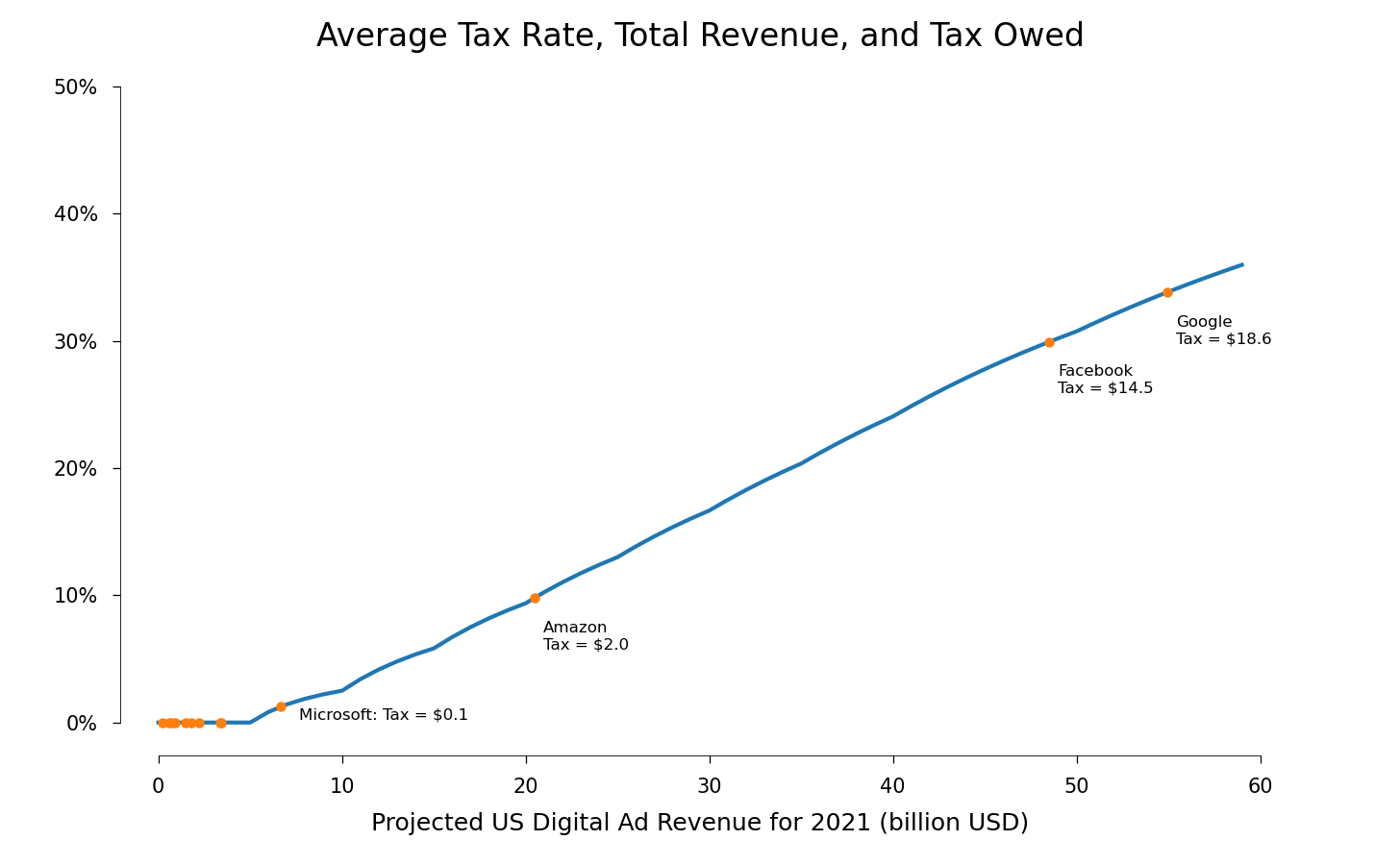

The blue line in the graph below shows how the average tax rate varies with revenue. It starts at zero, then increases steadily for revenue above $5 billion per year. Using published estimates of US digital advertising revenue for this year, the graph also shows the location of the firms that receive the most revenue from digital advertising in the US. Twitter is one of the unlabeled dots with an average tax rate equal to zero. Microsoft is the first labeled dot. The horizontal coordinate of its dot reflects its revenue of $6.7 billion. Its vertical coordinate shows its average tax rate. The number next to its label shows the tax that it owes in billions of dollars.

In this figure, the contrast between the large amount of tax that Google and Facebook would owe and the small amount that Microsoft and Amazon would owe highlights the effects of the choice of revenue from digital advertising as the base for the tax. Microsoft and Amazon collect far more revenue from other sources.

The graph shows that there is nothing "fair" about this particular tax. The circumstances call for the triage mentality of battlefield medicine. This tax focuses on the urgent challenge of preserving free political speech and democratic decision-making where action now could still make a difference. If this effort succeeds, our democracy can address the other monopolies in the near future. If it doesn't, effort devoted to limiting the other monopolies will have no effect. Best one can hope for is that the status quo prevails and that monopolies stop accumulating additional power.

In the spirit of triage, this version of the tax does not try to limit the use of the advertising model by small firms. Other than Google, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft, all the other players in this space -- Verizon Media (which owns Yahoo and Engaget), Hulu, Snapchat, Roku, Yelp, IAC (which owns such brands as Vimeo and Dotdash), Spotify and Reddit -- would pay no tax. They would face no immediate pressure for change, but would at least see that there are limits on the possibility of growth via this model alone.

The only goal of this tax is to push the firms that control digital advertising down the two paths that will reduce their political power -- the path toward subscriptions and the path toward competition between a large number of smaller firms.

Incentives for Change

The next table shows the recent and projected trend for US revenue from digital advertising for the entire industry and for Google and Facebook. The table that follows just after shows the tax that the entire industry and these two firms would have to pay under this tax system, taking as given the history of revenue and the projections through 2023. The right way to interpret these growing tax obligations is to think of them as the inducement that the government offers for switching to a model with no advertising that asks people to pay for the services they receive.

It takes a calculation to reveal the inducement that this tax system offers a firm to split itself into independent companies. For simplicity, consider a firm with US digital advertising revenue of $60 billion per year. Under this tax system, this firm would owe roughly $22 billion in tax. It could split itself into two firms, each with half as much revenue; roughly speaking, this is what would happen if Facebook were to spin out Instagram as a separate independent company. The two smaller firms would each face a lower average tax rate. The total tax bill for the two independent firms is $10 billion, which avoids $12 billion payments each year.

These two numbers capture the magnitude of the incentives that this tax system would create. A shift to a subscription model would save $22 billion per year in tax. Staying with the advertising model but splitting into two independent firms would save $12 billion per year.

Reasonable people can differ about the response that these incentives will trigger. Some people claim that that a tax bill for $22 billon would destroy both Google and Facebook. I find this hard to believe. If Google and Facebook each had to give up $22 billion from their 2021 earnings on ad sales in the US, their net receipts this year would be roughly equal to their total receipts in 2018.

The other concern is that $22 billion per year would not be enough to get these firms to give up on the advertising model. Given the steps that Google is taking and the success that other firms have had with the subscription model, it seems plausible to me that $22 billion per year would be enough to trigger a switch. But if not, the backup incentive -- $12 billion per year for splitting a company in half -- comes into play.

I can now explain the reason for the high marginal rates. In the next section, you will have a chance to recalculate the results presented above for any tax system you want to consider. If you click the Run button below the window with the code without making any changes, you can try a tax schedule that collects the same total revenue of roughly $22 billion per year from a firm with $60 billion in revenue and which caps the marginal tax rate at 50%. As you will see, the difference is that under this alternative, splitting the firm in two would save only $7.5 billion per year instead of the $12 billion in tax savings that the aggressive tax schedule would offer. So the system with the lower marginal rate creates the same incentive to switch away from a business model based on revenue from advertising, it offers a much smaller incentive for a firm that persists with this model to split itself in to smaller pieces.

Trying a Different Tax Schedule

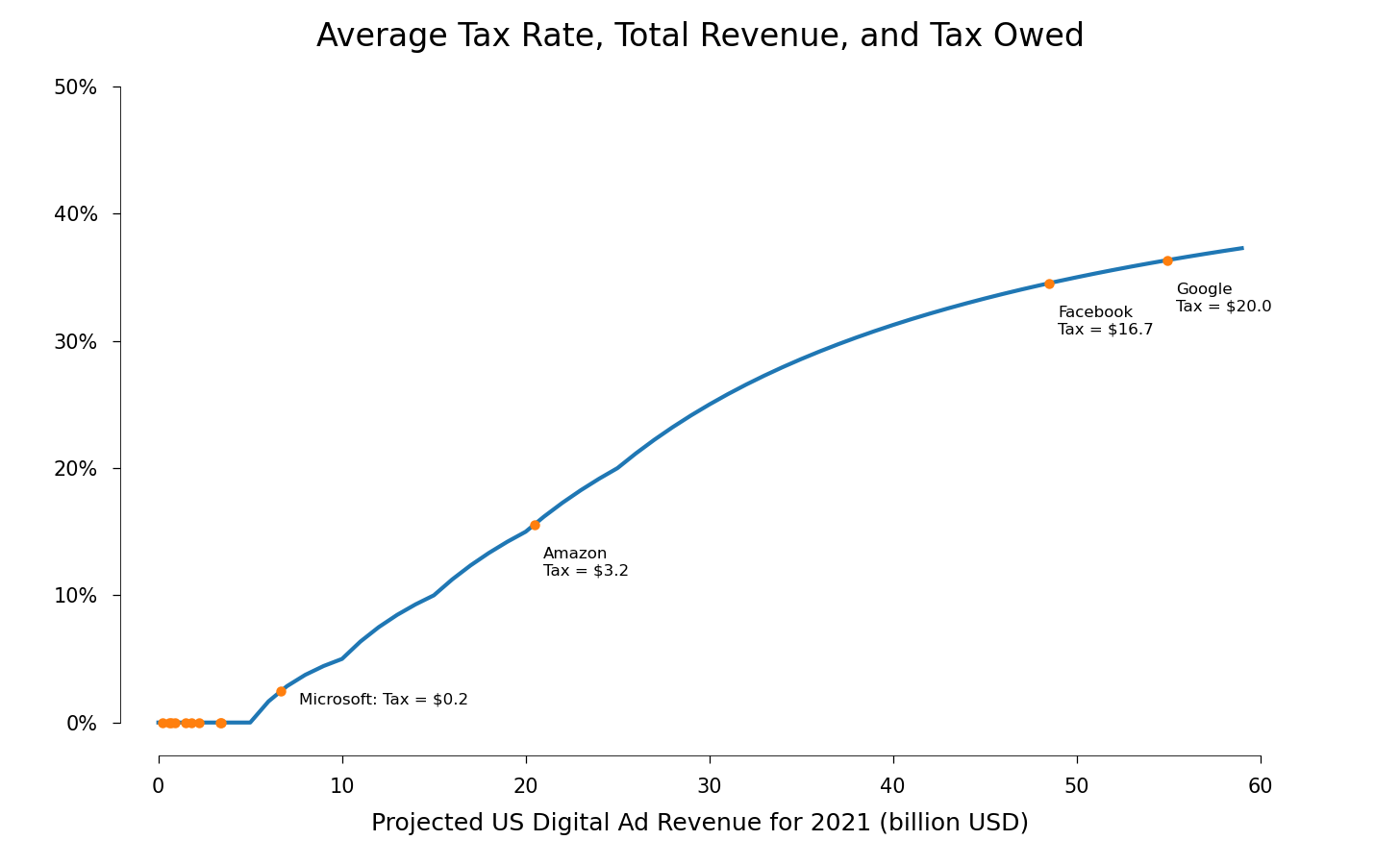

As the next schedule shows, it is possible to raise about the same revenue with a marginal rate that never exceeds 50%. The key difference is that the incentives for breaking up a firm are substantially lower. In this case, a split in half saves $7.5 billion per year instead of the $12 billion savings under the previous schedule.

If you leave the text in the window as is and just click the Run button, the tax system you submit will be the one that is specified on lines 10 and 11, the lines that do not start with the comment symbol "#". It caps the marginal tax rate at 50% and makes up the lost revenue by reducing the size of its tax brackets. If you edit the text in the code window, you can submit a completely different set of brackets and rates and redo all the calculations.

Before moving forward, please note these technical details:

- If you are on a mobile device or are using Safari as your browser, you will find newly calculated tables and inline values below the code window, browser limitations prevent the display of the corresponding graph. To see it, switch to a desktop computer that is running Firefox, Chrome or Edge.

- If you haven't encountered Python before, be forewarned that one of the conventions that makes Python so readable is that it assigns meaning to white space that indents blocks of code. One potentially surprising consequence of this design choice is that an errant blank space at the beginning of a line of code can render it meaningless. So if you delete some hash markers to activate some of the sample lines of code, check to make sure that you have not inadvertently add an initial blank space.

This table shows the brackets and marginal rates that you submitted when you clicked the Run button:

Under this tax system, a single firm with annual digital ad revenue of $60 billion faces a total tax bill of . If it split itself into two firms each with half as much revenue, their combined tax bill will be billion, which implies a reduction in the total tax bill of billion.

The next two tables repeat the summary of revenue and redo the calculation of the tax owed by the industry and by the two dominant firms.

As before, the graph displays the average tax rate for the tax schedule that you submitted. As in the previous graph, it locates the largest firms on this curve, and displays the total tax (in billions) that they would owe on their projected revenue for 2021.

If you do not see a Run button on the right, just below the code window, please be patient try refreshing the page or switching to Chrome instead of Firefox or vice versa. (NOTE ADDED OCT 4th: I've identified an intermittent problem where the browser never displays the `Run` button. If you encounter this and want to help me debug it, please feel free to get in touch via the inquiries page on my main website. AfterIf the Run button appears, when you click the button, the calculated results (in tables and inline in bold) will replace this placeholder text.

The Next Post

The next post in this series will reconsider the design of the ad tax that is based on worldwide digital advertising revenue. The gist of this analysis is that the United States stands to gain little from this revision, but it would confer a significant benefit on the other democracies in the world.

Closing Questions

The most important lesson from economics is that people respond to big incentives. The owners of Google and Facebook have a huge incentive to make sure that the tax proposed here is never adopted.

So if your initial reaction was that Google and Facebook would never use the advertising platforms and secret data that they control to influence the public debate on an urgent policy question, ask yourself these questions:

- How confident am I that either of these platforms would accept paid political ads that promote the ad tax outlined here?

- If one of these platforms did accept such ads, how confident would I be that they would serve these ads in a neutral way and treat them like any other paid political advertisement?

- After the fact, how could anyone verify whether such ads were in fact delivered as promised?